Liderança | Empreendedorismo | Gestão | Planeamento | Estratégia | Escrita para Financiamento | Especialista em financiamento para desenvolvimento | Orador internacional

20 de julho de 2025

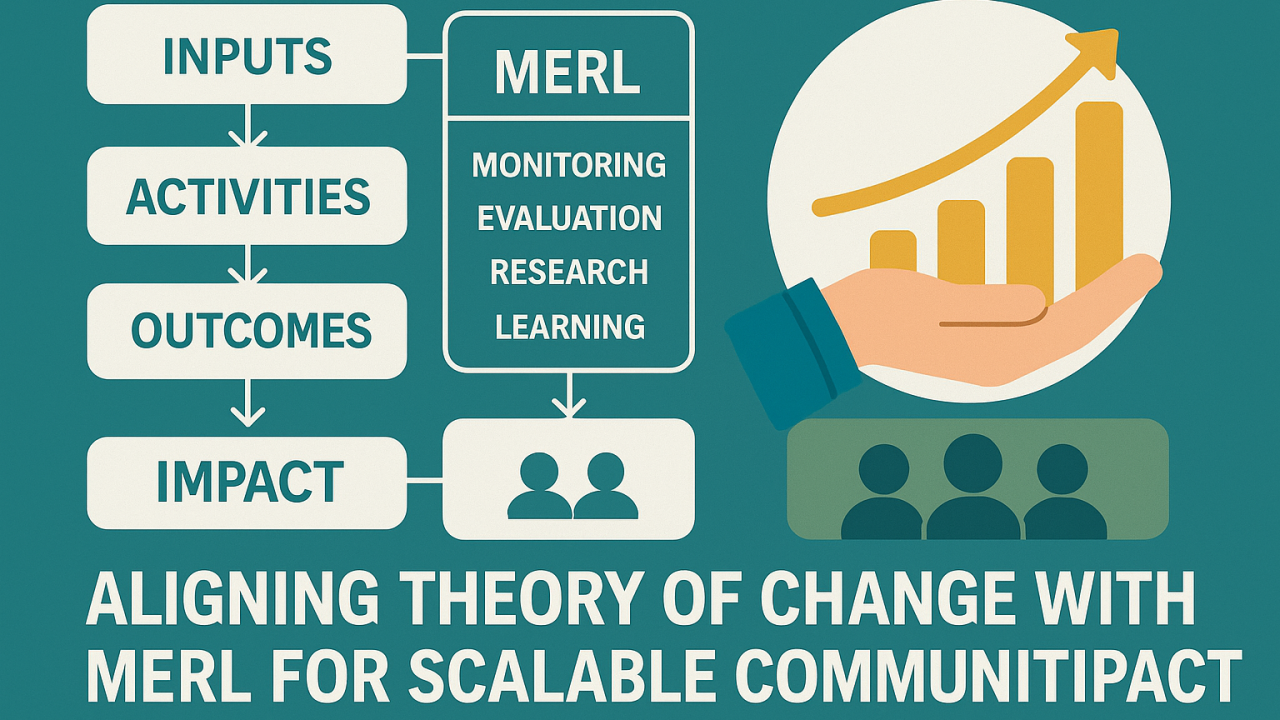

In the realm of community development, the pursuit of sustainable and scalable impact depends not only on the quality of programs but also on the ability to track, understand, and improve their effects. At the heart of this process lies the Theory of Change (ToC), a conceptual framework that articulates how and why a desired change is expected to happen in a particular context. When combined effectively with Monitoring, Evaluation, Research, and Learning (MERL) systems, the Theory of Change becomes a living tool—enabling reflection, learning, and strategic resource allocation that strengthens the path toward transformational community impact.

The Theory of Change is more than a logical model or a planning exercise; it is a strategic tool that connects intentions with measurable results. It clarifies assumptions, identifies preconditions for change, and maps out the pathways through which initiatives seek to achieve their long-term goals (Weiss, 1995). In community-based interventions, this mapping is especially important, as social impact often unfolds in complex, non-linear ways that require adaptive thinking and localized learning.

However, a well-designed Theory of Change on its own does not guarantee effectiveness. Its utility is significantly enhanced when embedded within robust MERL frameworks. According to Vogel (2012), integrating MERL with a participatory ToC approach ensures that data collection is meaningful, aligned with the programme logic, and responsive to contextual dynamics. Monitoring tracks progress, evaluation assesses effectiveness, research uncovers deeper insights, and learning supports decision-making and adaptation.

In many non-profit and community-driven organizations, this alignment is still underutilized. MERL is often seen as a compliance requirement or an afterthought, rather than as a strategic driver of learning and improvement. When MERL is siloed from the initial theory-building process, organizations risk investing resources into activities that are not effectively contributing to impact—or worse, missing the opportunity to scale what works.

Scalability requires evidence. Funders and institutional partners increasingly demand that initiatives demonstrate not only outputs and outcomes, but also the logic behind their strategy and the evidence that it is working. This is where a Theory of Change aligned with MERL plays a catalytic role. It enables program designers to identify leverage points, assess the viability of interventions across contexts, and generate credible data to inform replication or expansion. As Valters (2015) points out, “ToC can provide a bridge between the adaptive realities of development and the accountability pressures of donors.”

This bridge is essential in settings where community needs are dynamic and resources are limited. By fostering a culture of learning and reflection, organizations can continuously test and refine their hypotheses, ensuring that their efforts remain relevant and grounded in real change. Moreover, when communities are actively involved in defining, monitoring, and evaluating the pathways of change, programs gain legitimacy and resilience.

In practice, this requires investing time and capacity in both designing the Theory of Change and in establishing the MERL systems that will accompany it. These systems must be flexible enough to evolve, yet rigorous enough to provide credible insights. Crucially, the knowledge generated must not only feed upward to funders but also feed back into communities and teams for real-time learning and course correction.

Aligning the Theory of Change with MERL is not simply a technical exercise; it is a strategic imperative for organizations committed to community transformation. It enhances transparency, sharpens learning, and provides the foundation for scaling with confidence. In a development landscape increasingly driven by data, trust, and adaptability, this alignment offers a roadmap for making impact not only possible but powerful.

References

Valters, C. (2015). Theories of Change: Time for a Radical Approach to Learning in Development. Overseas Development Institute. https://odi.org/en/publications/theories-of-change-time-for-a-radical-approach-to-learning-in-development/

Vogel, I. (2012). Review of the Use of ‘Theory of Change’ in International Development. UK Department for International Development (DFID). https://www.theoryofchange.org/pdf/DFID_ToC_Review_VogelV7.pdf

Weiss, C. H. (1995). Nothing as Practical as Good Theory: Exploring Theory-Based Evaluation for Comprehensive Community Initiatives for Children and Families. In J. Connell, A. Kubisch, L. Schorr & C. Weiss (Eds.), New Approaches to Evaluating Community Initiatives: Concepts, Methods, and Contexts (pp. 65–92). Aspen Institute.